To be Black and to Succeed - Part 1

Christophe's story, an individual experience of the path to integration

I asked my friend Christophe if I could write his story. This is the not-so-trivial story of a successful Black man – the story of his experience behind the appearance of normality.

That was over a year ago. I had posted an article on LinkedIn explaining why I had left the company I had founded, Magic Makers. For the first time publicly, I mentioned racial and colonial trauma as an integral part of my experience, and committed myself to exploring these subjects more deeply.

It was a four-line paragraph in a multi-page article, which might have gone unnoticed by most people.

Christophe contacted me shortly afterwards. I realized from our exchange that the mere fact that I'd named these subjects in a LinkedIn post, in a space dedicated to the professional world, had had a huge impact on him.

So we started a double conversation.

On the one hand, it was a conversation about our experiences as Black people in France, our identity, and the construction of that identity over time.

On the other, it was a conversation about speaking out on this subject. What to say publicly? What can be received? What could have a negative impact on our careers?

Christophe has all the outward signs of success. Well-educated, he holds and has held positions of responsibility in major companies in France and abroad, with a high standard of living. He was a partner in a major international consulting firm. He is married, has three children, and is perfectly integrated, here and there.

But behind this social “success” image lies a much more complicated and painful story than meets the eye.

He himself told me: “Being black in a professional environment is like running a 100 meters race, starting 20 meters behind the starting line.”

It's these 20 meters that I wanted to make visible through his words. These are, for the most part, Christophe's words (in italics). I occasionally added my own words when I felt providing more context would be helpful.

This story is split into three parts, following the major stages of his life. Stay tuned for part 2 and 3, that I will publish in the coming weeks.

Part 1 - Youth

Growing up in a Housing Project

I grew up in a housing estate in the suburbs of Paris. At that time, the suburbs weren't like they are today.

My world was circumscribed by the housing estate, the neighborhood. We did everything inside. I had very, very little contact with the outside world, though we were on a metro line, directly connected to Paris.

I saw the neighborhood as a support for integration. At the time, about half of the people were second generation French, a quarter were white immigrants (Italian, Portuguese, etc.), and a quarter were “Arabs”* and Africans.

*Note: French people colloquially use the word “Arab” to designate people originating from the previous Maghreb French colonies and protectorates of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.

We celebrated Jewish, Muslim, Malian and Italian holidays. We invited each other and we were all together.

Later, little by little, the whites left the neighborhood, and were replaced by Arabs and Blacks, new immigrants. This created a real ghetto. It used to be a social ghetto, but not a cultural one. The people weren't well-off, but the different cultures mixed together.

At the time, I didn't experience racism. For me, racism is when someone attributes a certain skin color to you, and deduces that you're inferior to them.

That wasn't the case here. We called each other Arab, Black, “rital” (for italian)… We were the first to call each other names, but we were all equal. We weren't aware of what that meant. There was no malice.

The First Time I Realized I was Black

The first time I realized I was Black, or ugly, or both, was when I was seven. I was in the first grade, and I saw two new girls arrive, twins, and I thought they were beautiful. They've just arrived from Tahiti, and one of them, Ingrid, was like Barbie, blonde with long hair and blue eyes.

For my birthday, I went to see her and asked her to be my sweetheart.

She said no.

I said: “Okay, then what about your second sweetheart?

Then she listed all the people who came before me. It's a long list! She tells me I can be her sixth or seventh sweetheart.

I don't know if this is the first time I've realized I'm Black, or the first time I've realized I'm ugly. In any case, from that moment on, a link was created in my head.

I had the impression that I wasn't worthy of being loved, and part of me wondered if it was because I was Black.

(Note: Christophe is not “ugly”, despite his self-perception. In the same way, he regularly says he's not intelligent, which is contradictory to his diplomas and professional success, in an intellectually very demanding context).

The awareness that I'm Black, and that it's not necessarily a positive thing, grew gradually within me, and also in my interactions with other kids.

Back then, the ads we saw around were for Banania, Banga and Bamboula cookies. Advertisements with very colonialist imagery. I could see that the Black guy was the one carrying Jane's bag in Tarzan.

As I have an African-sounding name, I was given nicknames derived from it.

I fought against all the kids in the neighborhood to be called Christophe.

I must have been 10 or 12 years old, towards the end of primary school, the start of secondary school. I wanted to win that respect, I wanted to be Christophe, French, respected.

Social Selection is not Based on Merit

On top of all that, there were the messages sent to me by my parents, and their entire upbringing, which stemmed from colonialism.

Throughout my childhood and adolescence, what my mother said to me was:

“Ou ja nèg, pa fè sa “*.

*In Creole: “You're already a nigger, don't do that!”

It was her way of protecting me, telling me that I mustn't get into trouble, or they'd put me in jail, because I'm already Black. By definition, I'd be deemed wrong, so it's better to keep my mouth shut and keep a low profile.

And what I got from my father was that adults are always right. Authority can't be questioned, otherwise watch out!

At the same time, my parents told me, “You've got to climb the ladder.”

They said, “You're going to be an engineer”. At the time, I didn't know what it meant to be an engineer, but I understood that it was important.

At home, they made us listen to classical music and jazz. They took us to see exhibitions in museums, and to the theater too. On Sundays, my father made me watch the famous Sunday news show, 7/7, and asked me to write a summary for him. I owe him a big crush on Anne Sinclair, the journalist presenting it, and “intelligent” women in general.

At the same time, a sorting out began to take place among the kids in the neighborhood. By the end of primary school, there were virtually no Blacks or Arabs left; they were directed “elsewhere”. They were seen as troublemakers. Indeed, they weren't really troublemakers, they were just kids who needed help.

And my friends, I saw them dropping out one by one.

I had a good friend, Samir, there were 12 of them in his family, and he went to school with me. When we’d get home, I'd do my homework in half an hour and that was it. He had more difficulty, so he stayed at school for tutoring. He had good intentions, he wanted to get out of it. But he didn't make it. He didn't have the necessary support system at home.

When you come home and you're having trouble doing division and your parents can't help you, the split happens at that point, especially as you're then told you're hopeless.

I don't take credit for anything. These days, I hear people talk about class defectors, that it's all about personal success. In fact, I'm convinced that for 80 percent of your success, you have nothing to attribute to yourself, but to your environment, your family, cultural and social ecosystem.

In retrospect, I realize that even if I was in an environment that pulled me down, my parents really pulled me up.

The Tipping Point

I started high school in a good school. Up until then, I didn't have to work much to get good marks.

Now, all of a sudden it wasn’t enough anymore, and I started getting bad marks. I think I must have been the only Black guy in that place, or maybe there were just two of us.

One day, I got a super low mark in Physics. At the end of the first term, my teacher wrote a note in my notebook: “Doesn't meet the standard, how did he get in high school? Must repeat the year.” And he summoned my mother.

I remember I hadn't studied, I'd just stayed with my mates in the housing estate, playing. It used to be okay, but now it wasn’t.

My mother's a pharmacist, she's got a master in biology, and was a natural science teacher before.

When she arrived, the teacher addressed her as if she were uneducated, illiterate. My mother pointed out that she's a pharmacist, that she understood what he was saying, in short, she puts him in his place.

I was there thinking, “I'm going to get my ass kicked when we get home.”

But when we got home, my mother cried.

She said to me, “It's unacceptable Christophe, with all the effort I'm putting in to get you out of here, to get you there, you can't find anything else to do than to humiliate me and bring me home such a bad mark.”

I could see the disappointment in my parents' eyes. I could feel the gap between the fact that I was having fun every day in the housing project, and the fact that I was not living up to the potential or expectations my parents had for me.

I also suddenly realized that the teacher was sidelining me not only because I wasn't good enough, but perhaps also because of the way he perceived me: a Black guy, with all the connotations that go with that.

At the time, I didn't fully realize what my mother had gone through to become a pharmacist.

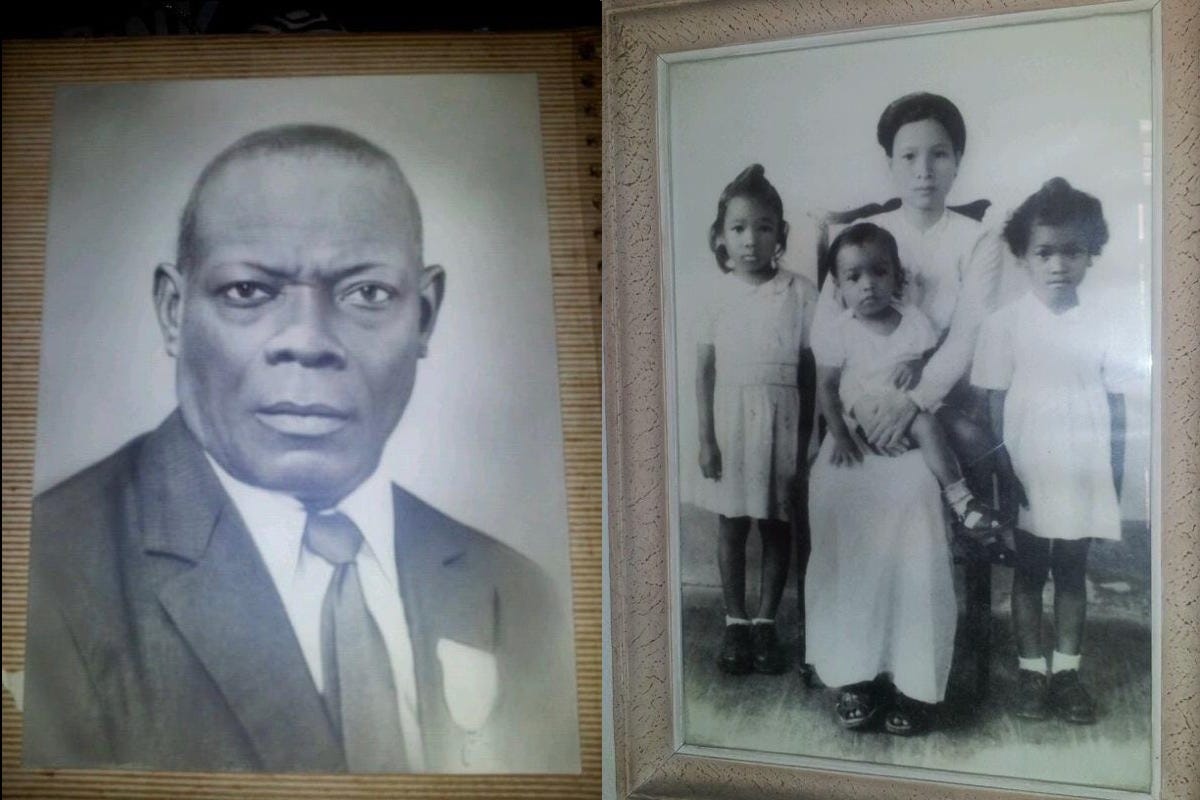

The Story of Christophe's Mother

Christophe's mother has an unusual story.

A woman of mixed race, Guadeloupean and Vietnamese, she crossed oceans and made a place for herself through education and determination.

Her father was from Guadeloupe, the French colony, and was a soldier in the Vietnam War. He had four children with a woman there. When the French army withdrew, he left Vietnam, leaving her behind. Christophe's mother was six when she arrived in Guadeloupe with him. She has no memories of either her mother or Vietnam.

In Guadeloupe, with her brothers and sisters, she was raised by her aunt. Her father, a countryside carpenter, remarried to another woman and was unable to look after the children he had brought back. They were different, and people called them “Chinese”.

When asked to describe the conditions in which his mother was raised in Guadeloupe, Christophe’s reference is the movie Sugar Cane Alley, by Euzhan Palcy (which received an honorary Oscar in 2022) : A gifted child at school, whose aunt does everything to ensure that she doesn't end up like the other children in the banana fields, or on the market selling them, and that manages to get out of poverty thanks to education.

At the end of high school, her mother won a scholarship and left her family, her culture and her environment, crossing the ocean to study in France. Her life changed from that moment.

There, she studied biology, graduating with a master’s degree. She wanted to go into medicine, but she married Christophe's future father, himself an African, and became a biology teacher. They had two children together, and as her husband finished his studies, they moved to Benin, to live with her husband's family.

But shortly after their arrival, Christophe's father died of an asthma attack. Christophe was just a few months old at the time. There, according to family tradition, a widow must marry her deceased husband's younger brother.

His mother refused, ran away from Benin and returned to France with her two children. There, determined to rebuild her life, she went back to university and enrolled in a pharmacy course, at the age of 34, and with two young children already in her care.

She became a pharmacist at the age of 38, and ended up owning her own pharmacy 10 years later, at nearly 50.

In the meantime, she met her new husband, a Cameroonian, who supported her on this path. Christophe calls him his father throughout this article, because he raised him as his own son, even though he is not his biological father.

Drugs and Violence, Christophe Cuts Ties with the Housing Project

The physics teacher's summons in high school was a turning point for me. From that moment on, I decided to cut all ties with the housing project. These two events happened at the same time: on the one hand, we moved and left the housing estate, and on the other, I repeated my second year at a new high school.

That's when I stepped out of childhood, out of innocence, and into adolescence.

Things had changed on the housing estate too.

Up until then, growing up in that place had been both violent and comfortable.

Violence had always been a social system there. Among the boys, there was a very clear ranking.

When a new guy arrived, you knew there was going to be a fight between him and the other guys in the gang. This was necessary to position him in the group.

I knew exactly where I stood, who I could beat, and who could beat me.

But with adolescence, things started to deteriorate. We used to get into some mischief and steal marbles. But then things started to get more serious, with stealing scooters and car stereos.

I didn't see drugs among people my age, who were 14 or 15 at the time. But it was starting to affect the older kids, my sister's friends, who were six years older than me. These were the guys I admired, the big brothers of the housing estate, and they fell into it.

Heroin took its toll on that generation. Two of my sister's friends died of overdoses, and three others fell over completely. I remember watching these guys, who were my heroes at the time, become physically stunted and lose their edge, without being able to clearly understand what was going on.

Once, we were playing soccer with each other on the estate, and one of them came up and asked us to give him a pass. He looked a bit strange, but we went along with it. But then he was so out of it that he fell in his stride and hit his head on the ground with a big 'Poc'. We scattered like sparrows! I can still see us coming back, hiding behind the cars to see if he got up again, if there was any blood or not. He stayed there for quite a while without anyone touching him.

The other thing I escaped was violence in relationships with girls. I think there were a lot of girls who had relationships that weren't necessarily consciously consented, but rather experienced as a necessity to belong to the group.

I was lucky enough to go through puberty very late, at 16 or 17, when I'd already left the housing estate.

But some of my mates started having relationships, and taking part in gang rapes. That's how a lot of them ended up in prison.

With the move, I started to leave that world behind.

I still went back to the housing estate from time to time to see my mates, but the distance between us was growing. I could see them falling further and further behind. They started to commit serious delinquency. Very few of them made it out. My friend Samir isn't one of them.

Envisioning Another World

On top of that, as around this time my mother was paying for us to go on language trips to England, I met other, more affluent young people. Some of them lived in apartments in Paris, and it was really a different world from the housing estate.

I was beginning to understand that there could be something else than the world I knew so far.

I used to say to these boys: “You don't realize how lucky you are!” And they didn't realize it, because for them it was normal.

I started to become envious.

On that trip to England, a friend of mine told me he was going to get into “Science Po” (Nickname to a very famous political science school in paris). I said “Science what?. You're doing science and politics? What's the deal, I don't get it.” I simply didn't know what he was talking about.

Inside me, there was rage emerging, anger rooted in “We don't have the same chances”.

“Graduate first!”*

*Literally, “Passe ton bac d’abord” is something French parents say a lot.

Older brothers on drugs, my mother crying, friends in jail, something changed.

When I started living in our new neighborhood, I didn't mix at all. I didn't have any friends. I think I went two years without speaking. I was completely focused on school work, and it’s all I did.

This time, we were in a “better” suburb. We were living in a bungalow, a bit out of the way of housing projects, and I stood observing from a distance. I turned my back on the housing estate.

“Now I'm Christophe, I have to respect my mother, I have to respect my father. I have to respect their work and I have to move forward.”

The way forward wasn't the housing estate, it was Paris, trying to become an engineer and assimilate, become “white”.

My silence during this period was a transition phase in which I lost the world of my childhood and entered a new world, with a greater awareness of a form of injustice.

During those two last years of high school, isolated in school, isolated in my new home, I graduated.

I got great marks, and was told I was one of the best.

Rage

During high school, my parents did not allow me to go out. I had friends who had cars, scooters, they went out, but not me. I could just go to the movies once in a while in the afternoon, and that’s it. I had to be home for dinner time.

When I was 18 and by the time I finished high school, I got my driving license. My mother said to me: "You graduated, now you can take the car. Go ahead and enjoy yourself, you deserve it." So I finally get to go out for the first time. The excitement is at its peak: I’m going out to celebrate my graduation, my 18th birthday, my license.

We got to the door of the nightclub, my friends got in, but I wasn’t accepted. I didn’t understand, I got dizzy. I asked why I couldn’t get in. They answered, “That’s the way it is, young man.”

It gave me a huge slap, the strongest punch of my short life! An incredible violence. I wanted to scream, shout, fight but I didn’t do anything. “Ou ja neg’” (“You’re already a nigger”)

Anger, rage, injustice and powerlessness began to engraft in me.

I’d done everything well, better than the others, I’d passed my high school diploma, I behaved, and yet I’m rejected. My white friends didn’t even have their diploma, let alone the marks I got, but they got into the club.

And that’s when I realize the privilege of being white.

Afterwards, I tried several configurations to get in : arriving with a beautiful tall blonde girl, with more white friends, but every time it was the same: the others would get in, but I wouldn’t.

White bouncers, Black bouncers, same thing. The only clubs I could enter were ethnic clubs, and the Queen (mythical gay club in Paris).

For regular night clubs, I finally figured out that if I wanted to get in, I had to arrive earlier, around 10:00 p.m. There was apparently an unspoken quota for Black people. When the quota was reached, Black people couldn’t get in anymore. Arriving around midnight at the same time as everyone else, didn’t work for me.

But from then on, I didn't want to go to places where I wasn't welcome.

I still feel the rage, and it won't leave me.

If you liked reading this, feel free to click the ❤️ button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack.

You can read on the next chapter of Christophe’s story below.